明治神宮ガイド Guide to Meiji Shrine 日英対訳 Japanese-English Translation 6

- 2018/02/03 03:12

明治神宮ガイド Guide to Meiji Shrine

日英対訳 Japanese-English Translation

目次/Contents

明治神宮の創建 / History of Meiji Shrine 7

明治天皇・昭憲皇太后 / The Meiji Emperor・Empress Shoken 7

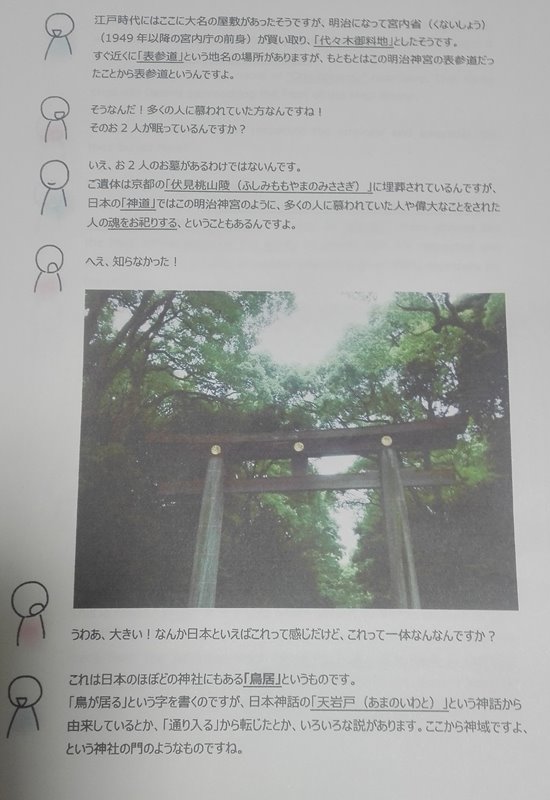

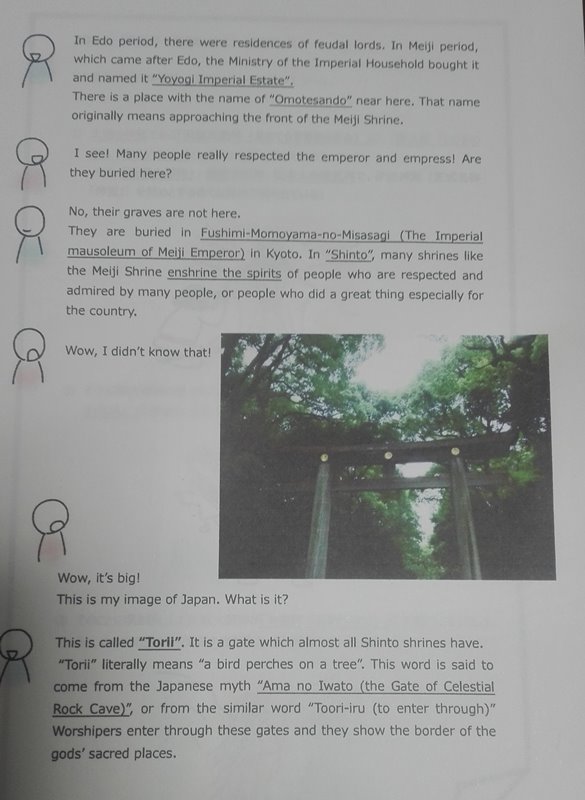

コラム①「天岩戸」のお話って? / Column 1. What is “Ama no Iwato (the Gate of Celestial Rock Cave)”? 11

菊紋・桐紋 / The Imperial crest of chrysanthemum・the Imperial crest of paulownia 19

正中 / Seichu (the exact center of shrine’s approaches) 21

狛犬 / Komainu (guardian dogs of shrines) 21

鎮守の杜 / The grove of the village shrine 27

酒樽 / barrels of sake and wine 33

コラム② 鳥居の基本 / The basics of Torii 39

和歌・短歌 / Waka・Tanka (Japanese poetry) 47

88度の角 / The 88 degree corner 49

手水舎 / Temizuya, Temizusya or Chozuya (purification trough) 51

神社での参拝作法 / The way to pray in Shinto shrines 55

お賽銭 / Osaisen (a small donation) 57

寺院での参拝作法 / The way to pray in Buddhism temple 59

神前結婚式 / Shinto-style wedding 69

夫婦楠 / a couple camphor tree 71

注連縄 / Shimenawa (sacred Shinto straw fastoon) 71

猪目(いのめ)/Inome (an amulet decoration) 75

お札・お守り・おみくじ / Ofuda(an amulet)・Omamori(a lucky charm)・Omikuji(a fortune paper) 77

縁起物 / Engimono (decorations for good luck) 81

コラム③ 御社殿の建築様式 / Column 3. The types of shrine’s buildings 87

車のお祓い / purification of cars 89

御苑・清正の井戸 / The Imperial Garden・Kiyomasa Well 91

BY SAE IIDA (https://www.facebook.com/chibisae)

この内容は、GLOBALCOMMUNITY 学生通訳ボランテイアガイド2017年リーダー、SAE IIDAさん(東京外大)が卒業論文として編集したものの一部を掲載したものです。

On Oct 9th, the 7th International Red-White singing Festival (IRWS) was held at the ‘Olympic Center’ in Tokyo and was authorized by the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affair, Tourism Agency and the Department of Tourism of the Philippines. Japanese Idols, Gospel groups, Kimono show participants performed, as well as some Asian and South American nationalities living in Japan.

It was quite a good opportunity for all contestants of different nationalities to be able to communicate with each other backstage. Even if one has lived in Japan for a long time, there was not much chance to be able to interact and mix; however, in IRWS, one has the opportunity to do so. Respect and appreciation for different cultures through singing in different languages, has drawn the performers, staff and audience closer. We have become like one big family with the staff and performers- may it be at the backstage, main stage and even with the audience.

The event started off with the performance of a High school Idol group, followed by the breathtaking performance of the Filipino contestant ‘KENICHI UANG’, a representative of IRWS in Cebu 2017.

A Chinese language study group, composed of native Chinese and Japanese performers, presented the World popular ‘PPAP’, with colorful costumes.

The Kimono fashion show was also very popular, especially amongst Asian girls.

‘Asian beauties become Japanese beauties with kimono on’

This was coordinated by Ms. Sheila Cliff -a University lecturer and qualified kimono-fitting specialist. She came to Japan more than 20 years ago and has been inspired by the beauty of Kimono since then.

Although they were not professional models, all girls were very relaxed and the show was really excellent.

In Part 2 of the program, a Peru female singer sang Enka (Japanese traditional song), while wearing a Happi (a traditional Japanese piece of clothing) and another Peru male singer sang ‘Kanpai’, a famous song at Japanese and Spanish weddings.

The special prize from Japanese Tourism Agency was given to Kenichi.

He was selected as the representative of IRWS in Cebu on the 6th of Aug 2017. Since then, he has been preparing for the Tokyo performance. Special support was given by the Cebu Music Learning Center, not only in the singing aspect, but also in the performance aspect.

IRWS has been widely covered by NHK ( Nippon Hoso Kyokai, Japanese national broadcasting). This time, it will also be covered by the International Radio Section wherein, the interviews of the contestants will be on air in English, Chinese, Spanish, and Portuguese.

Next year, the IRWS will be held in Cebu as well as Tokyo.

The International Red-White Singing Festival http://irws.org

We are looking for native English or Chinese speakers.

(Our team at the Monthly Lease division, with increasing numbers of queries from abroad)

Are you interested in working in real estate agency in the Shinagawa and Ota area, the international city that opens the door to a world of opportunities?

Your international background and experience would serve well in this position at City Housing Co., LTD due to multiple reasons, such as the upcoming Tokyo Olympics in 2020, expansion of Haneda International Airport, growth of international business, and rapid influx of visitors to Japan.

City Housing Co., LTD has over thirty years of experience and knowledge in real estate and owns around 10,000 rooms in Shinagawa and Ota area. We are committed to accommodating the diverse needs of our customers and expanding our business. We started receiving more queries from international visitors who are planning their stay in Japan for business or vacation.

You can achieve your goal to becoming an real estate professional by learning property management in many ways, such as self-storage, monthly rentals, parking lots, and renovation. The Japanese are so adroit at maximizing house space, and this is something you can learn and bring back to your country.

Real estate agents from China, Taiwan, Korea, and other Asian countries frequently come to visit Japan to learn our real estate business.

Please make the most of your new knowledge and experiences in real estate in Japan along with your language skills.

The position is only available at the Monthly Lease division at the moment due to the needs from international visitors, but there will be an opportunity for transfer to another division.

There are still very few non-Japanese with experience in Japanese real estate and we believe this would be an opportunity for you to build your career in Japan.

(We look forward to having new members on our team)

=====NEWS TOPIC=====

㈱シティ・ハウジングは、大田区を本拠地とするプロバスケットチーム『アースフレンズ東京z』のオフィシアルスポンサーを通して、バスケットで世界を目指す若者を応援しています。

選手との交流や、バスケット教室やスポンサー優待で観戦のチャンスもあります。

アースフレンズ東京z 公式サイト

http://eftokyo-z.jp/

求人概要 不動産総合職としての外国籍人材の採用

《対象となる方》

サービス精神が旺盛な方

時間をかけて、不動産のエキスパートを目指したい方

将来独立して、事業をおこしてみたい方

*なお、母国語と日本語以外に、英語でのやり取りが出来ることは必須です。

《勤務時間》

平日 9:00~19:00

水・土・日・祝 9:00~18:00(実働8時間)

《給与》

月給22万円(一律諸手当含む)

※経験者は月給25万円以上

※試用期間3ヶ月は、月給19万8000円以上(一律手当含む)

※宅建主任者資格手当あり(月額2万円)

経験が大変重要な業界ですし、仕事自体の専門性も高い仕事ですので、勤勉にじっくりと取り組めば、給与に反映される可能性も高く、また将来は独立するチャンスも多い職種です。

《昇給・賞与》

昇給年1回・賞与年2回・決算賞与 交通費全額支給・社会保険完

《休日・休暇》週休2日制(月6~8日)、夏季・冬季、産休・育休

《福利厚生》社内旅行(国内・海外のいずれか)・退職金・リゾートマンション(稲取、熱海、中里)・別荘(八ヶ岳)

株式会社シティ・ハウジング

〒144-0034 東京都大田区西糀谷4丁目28-14

http://www.cityhousing.co.jp/company/

《問い合わせ先》まずは、下記のアドレスに履歴書をお送りください。追ってご連絡をさせていただきます。

国際人材採用窓口

グローバルコミュニティー 宮崎計実

070-5653-1493

Globalcommunity21@gmail.com

http://yokosopan.net

Quoted from the article of BIG TALK between The Ambassador of the Kingdom of Bahrain to Japan Dr. Khalil Bin Ebrahim Hassan and the founder of APA GROUP Mr Toshio Motoya in APPLE TOWN

Motoya Various good systems existed in Japan in the past, but the U.S. rapidly changed them after the war. I am carrying out activities to regain these things. One of the systems I want to revive is the extended family system. If three generations lived together, various types of knowledge could be passed down from parent to child and grandchild. And even if the parents worked, the grandparents could care for the children. Conversely, children and grandchildren could also take care of their elderly grandparents. However, right now things have progressed from the era of the nuclear family to the era of the so-called “individual family.” I think we should use taxes to encourage people to return to the extended family system.

Hassan I think so, too. The Economist compared and analyzed the economic situation in the U.S., Europe, and Japan. The conclusion is that Japan was healthier than the other two regions. However, one problem is that Japan’s traditional customs are disappearing. Looking at the current situation in Japan ? in which almost 25% of the population is age 65 or older ? it is foreseen that a large amount of money will be spent caring for these people. Perhaps one measure to resolve this problem would be the revival of the extended family system.

Motoya Yes. Japan was originally a tribal society centered on blood relations. I’ve heard the same thing applies to other places like the Middle East. However, the focus has shifted to individual families due to waves of Westernization, resulting in the creation of a high-cost society.

Hassan The doctrine of extended families is an important one. In Japan today it is a problem that people don’t often get married and have children. If the number of single elderly people increases, I think that society will be moved in a strange direction. It may be necessary to urgently promote the extended family principle.

Motoya Yes ? families would definitely become happier. Extended families would help resolve the problems of people who die alone or are homeless. Conversely, individual family divisions create increased costs and feelings of loneliness. In life there is nothing more important than family.

quoted from APPLE TOWN published by Mr Motoya founder of APA GROUP

http://www.apa.co.jp/appletown/bigtalk/bt1208/english_index.html